The Power of Community

The Jacka 2 community battery: An Analysis

Download the full report here

Governments and energy companies are increasingly interested in a new form of community-scale energy storage, known as a community battery. It has the potential to solve some of the significant issues faced when trying to integrate greater amounts of renewable energy into the broader electricity network, while increasing access and reducing costs for a wider range of users. In a broader sense, systems like community batteries could help drive a fundamental paradigm shift around energy by establishing energy generation as a local and collective activity, while driving a broader global movement that could address some of the most complex challenges of our time - a necessary and urgent transition to a zero-emissions society.

Context.

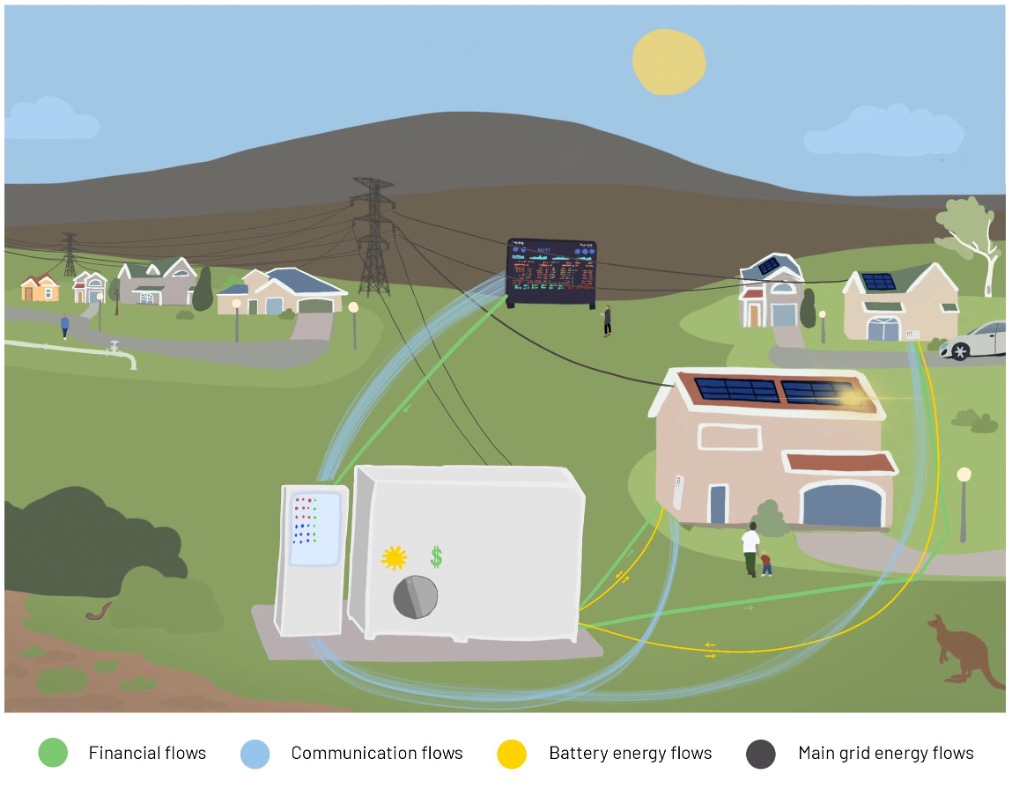

With a capacity of 100kW to 5MW, community batteries are a form of community-scale energy storage. Physically about the size of a shipping container, a community battery is designed to be accessed by multiple users, typically houses with their own individual solar photovoltaic systems, enabling them to store excess energy generated by the households’ solar panels during the day for later use - effectively a demand management service.

The home of the first community battery on the east coast of Australia may be on traditional Ngunnawal country in the suburb of Jacka in Canberra’s north. In designing a new phase of the suburb, called Jacka 2, the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) Government plans to connect solar panels on each house to a shared community battery that charges and discharges based on machine learning algorithms.

As a new type of cyber-physical system, there are a number of ways the community battery can be optimised - to make a profit, reduce the energy bills of participants, store the excess solar energy being generated locally or smooth out peaks in demands. It is difficult to realise all of these goals simultaneously due to trade-offs that exist between them, demonstrated by the initial modelling of four different scenarios of use based on different ownership structures. This presents the ACT Government with the challenging task of deciding how to optimise and for whose benefit.

Increasing energy equity is of growing importance to the ACT Government as part of its commitment to developing zero emissions suburbs and realising broader sustainability goals. But without adequate community involvement, the battery may be deployed inequitably and may be economically unviable. If some of the possible for-profit models are realised, community benefit and involvement may be entirely absent, making it simply a battery system, as opposed to a community battery system. Yet it is difficult to establish community values, priorities and preferences since the community at Jacka 2 is yet to exist. Therefore this research asks:

How can the community battery in Jacka 2 be scaled from concept to reality in a safe, responsible and sustainable way that prioritises the interests of the Jacka 2 community despite the absence of that community at the present time?

We apply a combination of six different research methods and consider potential emergent properties to offer the ACT Government six key recommendations about how to more comprehensively consider the needs and wants of the future Jacka 2 community inviting them into the development and design process. In doing so, the community battery has the potential to grow identity and a sense of ownership around this system contributing to a fundamental shift in the perception of energy generation as a local and collective activity.

Summary of recommendations

-

Engage, and engage now.

The ACT Government needs to engage, and engage now, to adequately map localised community needs, preferences and requirements, build decision-making capacity regarding operational and optimisation models and grow buy-in for the project.

Informed by the following research methods: Leverage Points, semi-structured interviews, direct and indirect stakeholder mapping. -

Communicate how it works.

The ACT Government should build community understanding and engagement by developing tools to communicate the intent of the community battery system, how it works and what impact it will have.

Informed by the following research methods: Leverage Points, semi-structured interviews, direct and indirect stakeholder mapping -

Don’t focus on models, focus on values.

In thinking about the design of this battery, and when communicating it, we recommend that its designers think and talk primarily in terms of the values it embodies and promotes, rather than how the model works.

Informed by the following research methods: direct and indirect stakeholder mapping, Country Centred Design -

All in: reconsider opt out.

Reconsider the value of offering an opt-out mechanism for the community battery at Jacka 2.

Informed by the following research methods: semi-structured interviews -

Appearance and placement matter.

In selecting the location and appearance of the community battery, the ACT Government should avoid producing inequities and explore opportunities to validate and reinforce a sense of ownership and collective activity through the battery’s physical presence.

Informed by the following research methods: observation, semi-structured interviews, Country Centered Design, speculative fiction. -

Interfaces matter.

Implement an interface as part of the community battery system for optional usage by participating households.

Informed by the following research methods: Leverage Points, semi-structured interviews, speculative fiction.

The complexity and adaptability of cyber-physical systems makes communication and decision making particularly challenging. These recommendations are offered as a way of viewing these complex decisions through a community lens while highlighting opportunities for far deeper engagement with the system. The outcome at Jacka 2 has the potential to offer a unique test case for not only the details of the technical deployment but also of a community engagement model that ensures the safety, sustainability and responsible deployment of community batteries elsewhere.

Conclusions

Community batteries offer an opportunity to shift fundamental perceptions of energy generation, by establishing it as a local and collective activity, while driving a broader global movement that could address some of the most complex challenges of our time - a necessary and urgent transition to a zero-emissions society.

The Jacka project will provide an invaluable test case for a range of operational models and optimisations that offer a complex set of trade-offs between different sets of values. The choice of model will determine which of a range divergent futures materialises for Jacka 2, potentially offering residents significant savings on their energy bills while building a strong sense of community identity as the beating heart of an innovative and sustainable new suburb.

New kinds of systems powered by machine learning present an increasingly complex set of choices and risks for developers that did not exist with more traditional systems. The various ways in which algorithms can be optimised raises multiple questions: Whose goals and values is the optimisation aligned to? Why is it being optimised in that manner? Who makes the decision on how it is optimised? Who benefits from the optimisation and who may be disadvantaged by it? Can the system be trusted to work fairly? During the design and management of the system, tensions and conflict may arise from the multiple choices available. This is difficult to communicate and end users can feel overwhelmed by the level of information, level of technicality and number of alternatives they need to assess in order to be left with a fair, efficient, cost-effective service. Meanwhile, making safe, responsible or sustainable evaluations of and decisions about the boundaries or limitations of a system can also sit in opposition to modern philosophies about the consumer’s right to choose - something the ACT Government is currently navigating at Jacka 2.

And these decisions matter.

As one of the first batteries on the east coast of Australia, the Jacka 2 project could provide other jurisdictions with not just a technical use case for this technology, but also a community engagement pathway for implementing their own community batteries in a way that is responsible, sustainable and safe.