Exploring a cyber-physical system

Guardian™ Connect Continuous Glucose Monitor

Infrastructure and Resources – Cyber Physical System (CPS) Poster

The Guardian Connect CGM is a continuous glucose monitoring system (CGM) designed for people who have insulin-treated diabetes. The system consists of a sensor which is inserted under the skin, a transmitter which is worn on your body, a smartphone app, algorithms to predict high and low glucose levels, a centralized data storage. The transmitter sends data from the sensor to the app, allowing a near-real-time stream of data on the wearer’s blood glucose levels. The Guardian™ Connect CGM also uses ‘smart technology to predict where your glucose levels are headed [and] will alert you from 10 to 60 minutes before a high or low’. The system costs around $5000 per year for the transmitter and sensors. The sensor must be replaced regularly (every 7 days). The Guardian Connect is purely a monitoring device – it does not replace the need for pin prick tests (for both calibration of the device and insulin injection).

The basic operation of this System is: using a sensor under the skin, it measures the amount of glucose in the interstitial fluid. This data is then sent through Bluetooth to a smartphone. In the Guardian™ Connect App one can see the near-real-time information. It is important to note that it is near-real-time because the readings are made every 5 minutes, up to 288 readings per day. This data is also uploaded to a website in which the user or any other person that has is able to track the glucose levels.

For this task, we were asked to create a poster that represents what infrastructure and resources are needed to use or work with the CPS, as well as understanding the technical and human requirements for it to work properly.

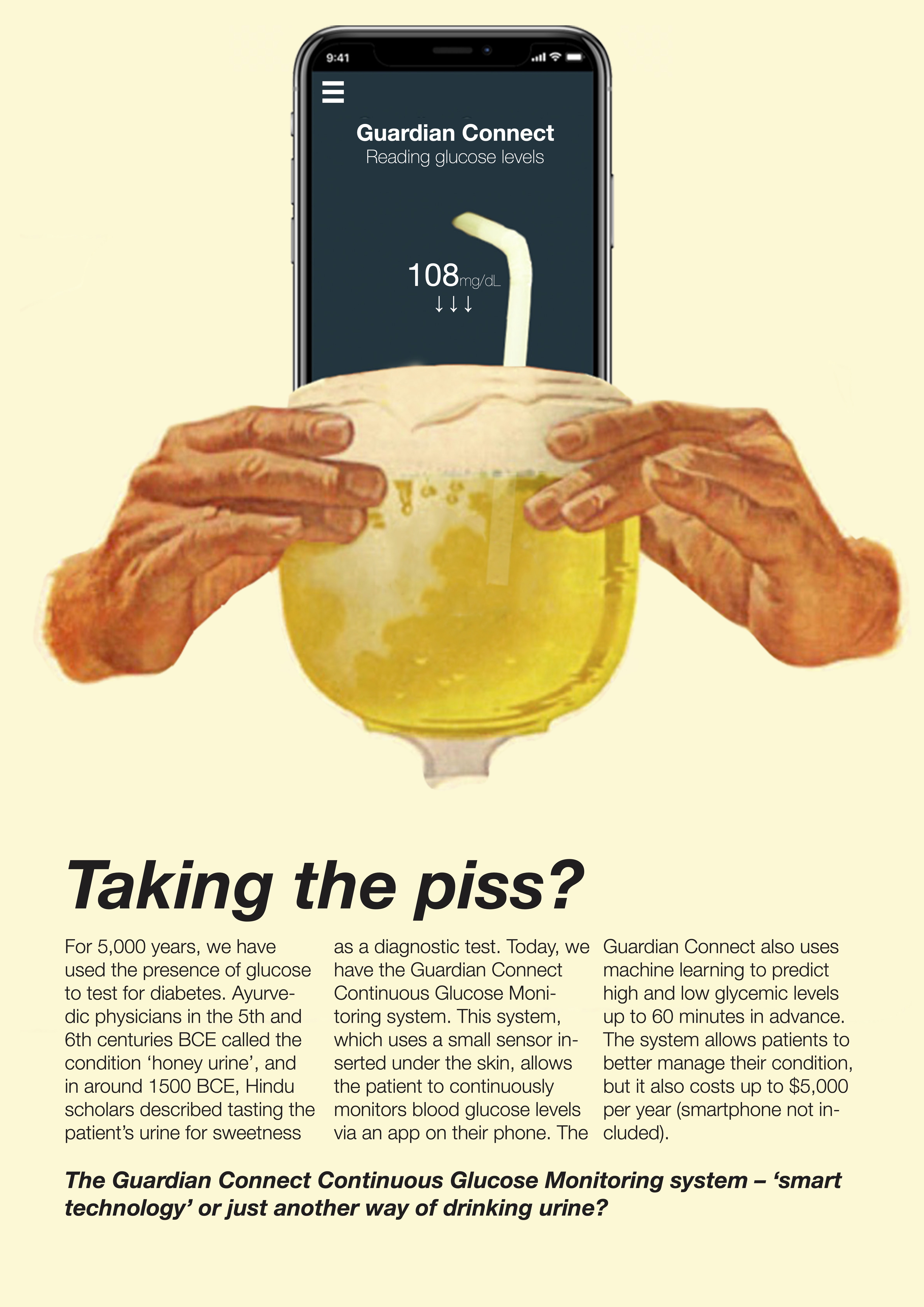

The approach we took as a team was to use historical methods to detect diabetes, given that the disease has been around for more than 5000 years, and contrast them with the CPS. Aiming to compare the interstitial fluid measure to drinking urine (earliest known method to detect diabetes).

Guardian™ Connect CGM Poster V1.0

PDF Version Here

The feedback we received was focused on improving our metaphores, since they were not too obvious to understand them without having to read or do research about the system.

From this point all the work and iterations were made by me.

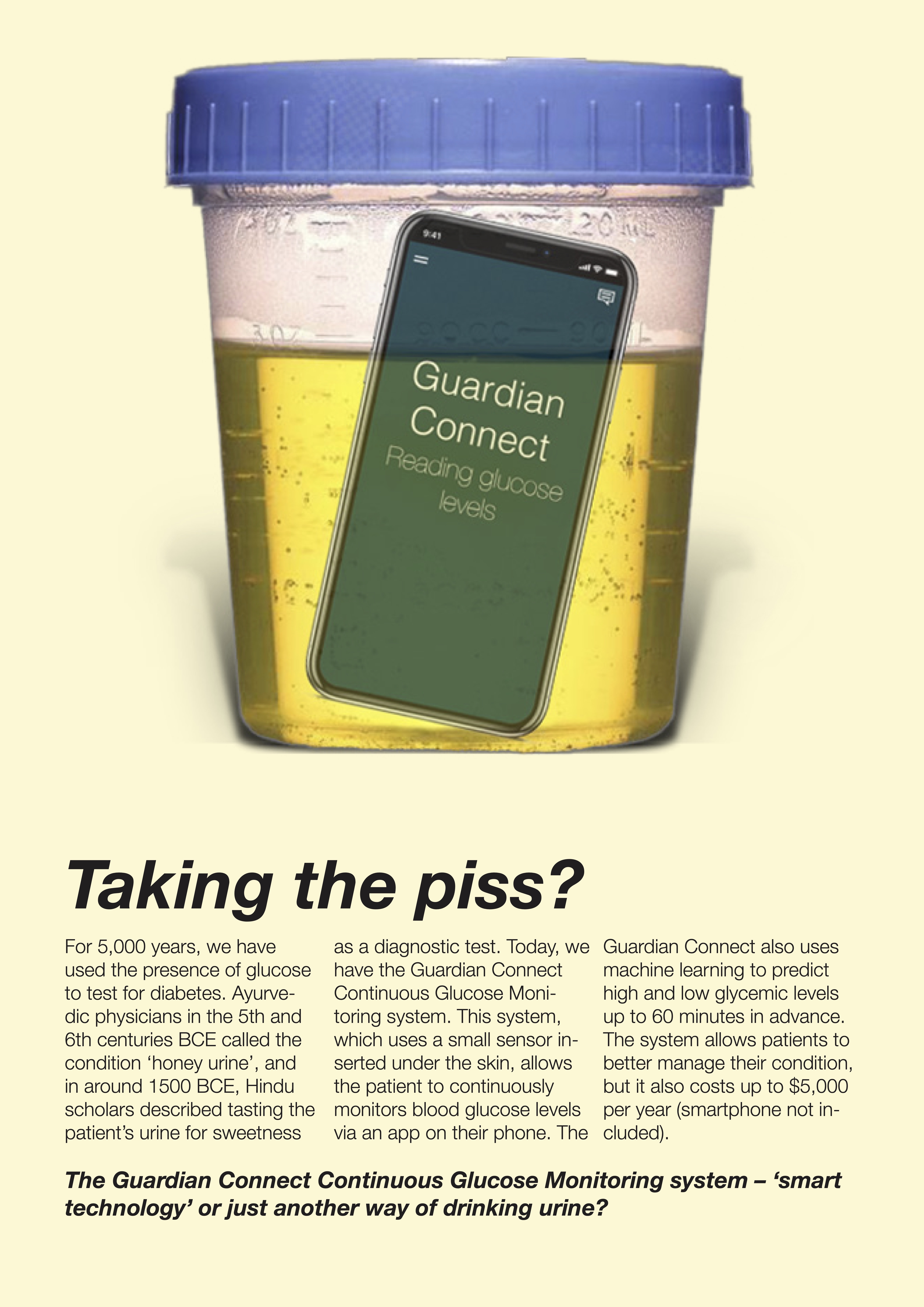

After some iterations, wondering what visual aspects could better convey the message, I decided to use a urine collection cup instead of the beer-like glass. This new metaphor could have a strong message and a subtle shocking element, enough to draw attention from the viewer.

Guardian™ Connect CGM Poster V1.1

PDF Version Here

Although I think the poster is good, I wanted to explore another approach: using familiar images, I tried to convey the message of some of the unspoken requirements and unexpected outcomes of the system. Some of these are the environmental cost of having an active Bluetooth connection 24/7, where the data is stored, what might cause interference to the system (and what other systems might have interference), etc. The third version of the poster is:

Guardian™ Connect CGM Poster V2.0

PDF Version Here

Questions raised while doing this task:

The system offers a value proposition for the lives of people using the device, and it has an impact on improving their daily routines. However, given its price, this system is only accessible for those who can afford it.

With a rating of 1.7/5 stars on the Apple AppStore and 1.8/5 on Google’s Play Store raises the question about the ease of use of this system. Given that application is an essential part of this system, one would expect it not to be perfect (because some problems might arise]) but this low rating could make a potential user question if this system is really useful for them.

Related to the last point, many reviews and complaints about in both stores are related to the lack of upgrades or compatibility with the latest phones and how little support is offered by Medtronic. If this is one of the leading products of the company, shouldn’t the post-sale service be exceptional? Which leads to the next question.

Is this a short-term solution or a long-term device? Both questions should be addressed and both questions have serious implications as well. For instance, if this device is intended to be used for a long time, what are the efforts that the company is making to ensure access to support, new firmware and software versions, and, in general, how to avoid programmed obsolescence. On the other hand, if this is a short-term solution, what is the environmental cost of having a large number of electronic components disposed of in a small period of time? Does more availability of the solution imply a cheaper option? How and what makes this system different from blood strips testing?

Is this device solving a problem or is it just a luxury for a few? Considering that a user needs to have certain technologic devices and/or infrastructure (such as internet connection, smartphone, etc) and they are not available for everyone, it raises the question if this is merely a profit-driving system instead of a health technology that could be available for everyone.

This device is approved by the FDA, but legislations and requirements change from country to country. For instance, some laws might forbid health data to be physically outside a country. From Medtronic’s webpage, data coming from this system is stored in the USA, Singapore, the Netherlands, and/or Switzerland. In countries where legislation is very strict about this, the system may not be available or even useful.

The Sugar.IQ™ is the personal diabetes assistant that Medtronic offers as an add-in for Guardian™ Connect. It claims that it can predict when a user is more likely to have a low or high level of glucose up to 60 minutes in advance. According to its website, it uses IBM Watson™ and diabetes expertise from Medtronic. Nevertheless, it is not stated how these predictions are made, what datasets are used to perform the analysis and pattern detection, or how this could work for one person while it could not for others. Speaking about datasets, it would be really interesting to compare how this algorithm behaves with people included in the dataset compared to people which are not, in terms of geographic presence, race, gender, age, etc.

Training AI algorithms can use a big number of resources in terms of computational power and environment cost. Research suggests that AI-related activities are accountable for 2% of all global carbon emissions. Keeping in mind that this system is available only for a few and that it requires datacenters and training algorithms, it raises the question of what is the real cost of this system? Is it worth it?

These questions do not have a right or wrong answer but rather are intended to be a guide when analysing cyber-physical systems.

References used:

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2019, Incidence of insulin-treated diabetes in Australia, viewed 14 March 2020, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/diabetes/incidence-insulin-treated-diabetes-australia-2017

Ballantine Ale 1953, Different cowboy ad, viewed 15 March 2020, https://www.madmenart.com/wp-content/uploads/Ballantine-Ale-Different-1953-Cowboy.jpg

Harvey R 1998, The Judgement of Urines, JAMC, 159(12), 1482-1484

Karamanou, M., Protogerou, A., Tsoucalas, G., Androutsos, G., & Poulakou-Rebelakou, E. 2016 Milestones in the history of diabetes mellitus: The main contributors, World journal of diabetes, 7(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v7.i1.1

Lakhtakia R 2013 The history of diabetes mellitus, Sultan Qaboos University medical journal, 13(3), 368–370. https://doi.org/10.12816/0003257

Mandal, Ananya 2019 History of diabetes, viewed 14 March 2020, https://www.news-medical.net/health/History-of-Diabetes.aspx

Medtronic 2019, Guardian Connect, viewed 14 March 2020, https://www.medtronic-diabetes.com.au/products/guardian-connect MacCracken J (guest editor), Hoel D & Jovanovic L 1997, From ants to analogues, Postgraduate Medicine, 101:4, 138-150: DOI 10.3810/pgm.1997.04.195

National Diabetes Services Scheme (NDSS) 2020, Continuous glucose monitoring, viewed 14 March 2020, https://www.ndss.com.au/about-diabetes/resources/find-a-resource/continuous-glucose-monitoring-fact-sheet/

National Diabetes Services Scheme (NDSS) 2020, Continuous glucose monitoring, viewed 14 March 2020, https://www.ndss.com.au/about-diabetes/resources/find-a-resource/continuous-glucose-monitoring-fact-sheet/

Saxena, Shikha 2017, The distribution and global burden of insulin dependent diabetes mellitus, Journal of Pharmacy and Biological Sciences Vol 12, no. 4 pp 40-48.